Inspiration

I recently finished an audiobook of the first volume of The Civil War: A Narrative, a meticulous work of military history written by Shelby Foote. The three volumes comprise nearly 3,000 pages and 1.2 million words, so it may be a while yet before I finish the entire trilogy. Nonetheless, I have thus far enjoyed the detailed, direct writing style of Foote and his characterizations of the famous leaders on both the Union and Confederate sides.

In Foote’s narrative, whenever the backstory of another military leader is presented, more frequent than not his service record began along the Hudson River at West Point. Case in point – all 60 major battles of the war were commanded on at least one side by a West Pointer.

Questions arose in my mind, foremost of which were the following: which classes were most successful in command held during the Civil War? Was there a correlation between West Point graduation rank and command held?

West Point and the Civil War

Of the more than 200 graduating classes in the history of West Point, there have been two classes retrospectively recognized as special. These were each termed as “the class the stars fell on,” as a large proportion of graduates went on to obtain star(s) of generalship. The two classes were the class of 1886 and the class of 1915. Of the class of 1886, 25 out of 77 went on to become general officers, mostly serving during World War I, including John J. Pershing. The class of 1915 was even more decorated, as 59 out of 164 graduates eventually attained the rank of general, most famously Dwight D. Eisenhower and Omar Bradley.

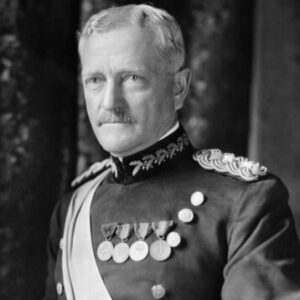

John J. Pershing (1860 – 1948)

Class of 1886, Rank 30/77

“Black Jack”

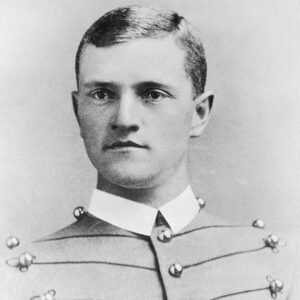

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890 – 1969)

Class of 1915, Rank 61/164

“Ike”

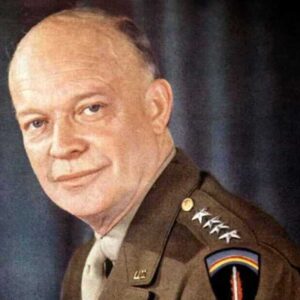

Omar Bradley (1893 – 1981)

Class 1915, Rank 44/164

“The GI’s General”

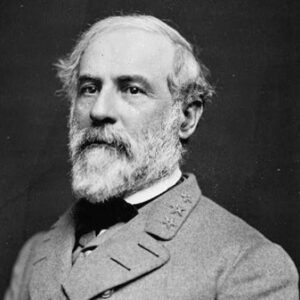

I am a bit surprised that none of the classes that predated the American Civil War was ever known as a “class that the stars fell on.” After all, in a civil war, there are not one but two sides that require generalship! In point of fact, Robert E. Lee, best known for his command of the Confederate States Army in the latter stages of the war, was first offered a position as major general of the Union forces. His response is telling of the conflicting ties that many in the border states felt at the onset of the war:

“I look upon secession as anarchy. If I owned the four millions of slaves in the South I would sacrifice them all to the Union; but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?”

§

From this analysis, I used extensively the website Civil War in the East, which was indispensable in providing the raw tables of graduation year, Civil War command held, and graduation rank of cadets. I was aided by a web scraper add-on with Google Chrome.

There were a total of 56 West Point classes that sent soldiers into the Civil War, the earliest of which was the 1805 class and the last of which was the 1864 class. West Point did not have a graduating class of 1810 and 1816, and none of the classes of 1802, 1803, 1804, 1807, 1809, or 1813 had graduates who participated in the Civil War. There were two classes of 1861, in May and June; the latter was an accelerated class that originally would have graduated in 1862, but was graduated early for purpose of the war effort.

From 1802 to 1864, a total of 2046 cadets graduated from the United States Military Academy, as gauged by their Cullum number. Of the 2045 cadets, 1122 of them, or 54.8% participated in the American Civil War.

As an aside, it is interesting to see the progression of class size at West Point, from two cadets in the initial class of 1802 to 1014 cadets in the class of 2022, by itself nearly the number of West Point graduates who eventually went on to serve in the American Civil War!

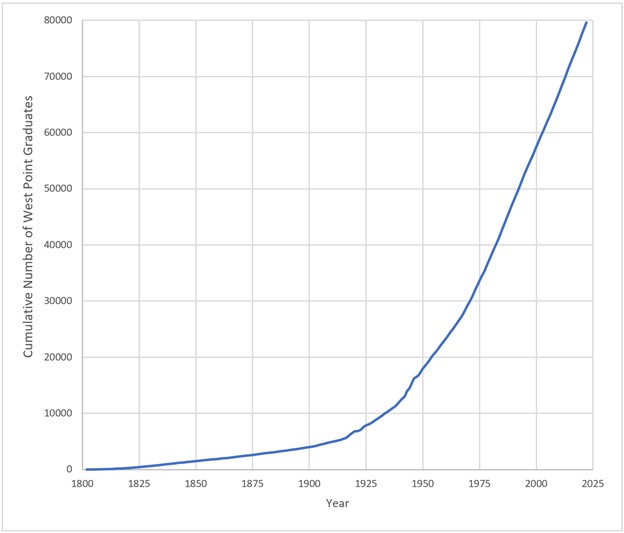

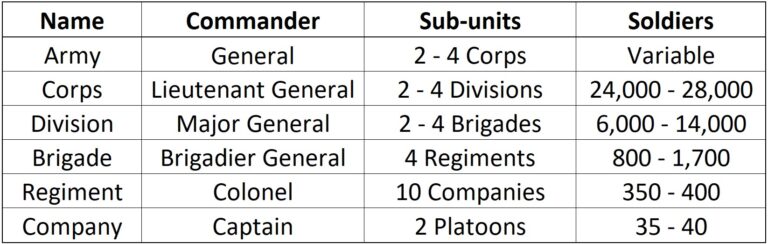

The structure of the Union and Confederate Armies during the Civil war can be confusing at times, and before continuing further with the results of the data scraping, let us first visit the topic of command structure.

Upon graduating from the United States Military Academy, the soldier would be commissioned in a junior officer role as a Second Lieutenant, in charge of a platoon (~20 – 40 soldiers), assisted by two sergeants and two to four corporals. From here, the soldier could advance through promotion to other junior officer ranks (first lieutenant, captain), then senior officer ranks (major, lieutenant colonel, colonel), and finally flag officer ranks (brigadier general, major general, lieutenant general, general).

A table for the tactical organization of the Union Army is presented below. The unit sizes given are full-strength, though attrition due to a variety of reasons could drastically change the number of actual soldiers in the field.

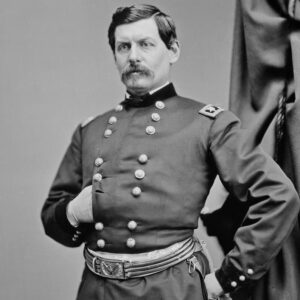

The rank of Lieutenant General in the Union Army was only created in February 1864 by Act of Congress, and they generally undertook command of whole armies. Over the course of the Civil War, there was a total of four General-in-Chiefs on the Union side: Winfred Scott, George B. McClellan, Henry Halleck, and Ulysses S. Grant, the latter three of whom attended West Point.

Winfred Scott (1786 – 1866)

College of William and Mary

“Old Fuss and Feathers”

George McClellan (1826 – 1885)

Class of 1846, Rank 2/59

“Young Napoleon,” “Little Mac”

Henry Halleck (1815 – 1872)

Class of 1839, Rank 3/31

“Old Brains”

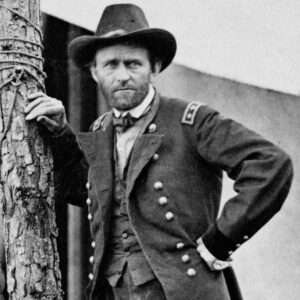

Ulysses S. Grant (1822 – 1885)

Class of 1843, Rank 21/39

“Unconditional Surrender”

To make matters more complicated, the Union Army was divided into Regular units and Volunteer units. At the onset of the Civil War in April 1861, there were only 16,400 soldiers in the standing Regular Army. Over the course of the American Civil War, while the number of soldiers in the Regular Army only increased to approximately 20,000 in number, that of the Volunteer Army numbered over a million by war’s end.

In terms of command, Regular general officers outranked Volunteer general officers of the same rank, even if the Volunteer officer had “seniority” by basis of date of commission. In addition, the Union Army made use of brevets throughout the war, an award designating gallantry or meritorious service without conferring actual command.

To little surprise, the structure of the Confederate States Army was based on that of the United States Army, with a Regular Army and a Provisional (volunteer) Army alongside Confederate State Militias. The size of units in the Confederate States Army was generally smaller than their Union counterparts:

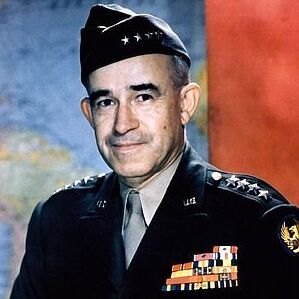

A total of seven graduates from West Point went on to become full generals in the Confederate States Army. I could only find nicknames for two of them, so only photos of those two will be included in this post.

Interestingly, these seven generals graduated from West Point from the years 1815 to 1838. In the Union Army, in contrast, the three highest-ranking West Point graduates were from the years 1839, 1843, and 1846.

Robert E. Lee (1807 – 1870)

Class of 1829, Rank 2/46

“Granny Lee”

P. G. T. Beauregard (1818 – 1893)

Class of 1838, Rank 2/45

“Little Creole,” “Little Napoleon”

Contrary to that of the Union Army, the Confederate States Army did not designate any brevet ranks for the duration of its existence. Since the website that I used for officer ranks provided the actual rank in the Union Army, rather than brevet rank, this saved me the hassle of going through each Union general’s service record to check if he obtained his rank through brevet or standard promotion.

After the initial web scrape, I found that a total of 371 graduates obtained a general rank (brigadier general, major general, lieutenant general, or general), broken down into 221 within the Union Army and 150 within the Confederate States Army. I excluded those who served in a generalship capacity within the Union and Confederate state militias.

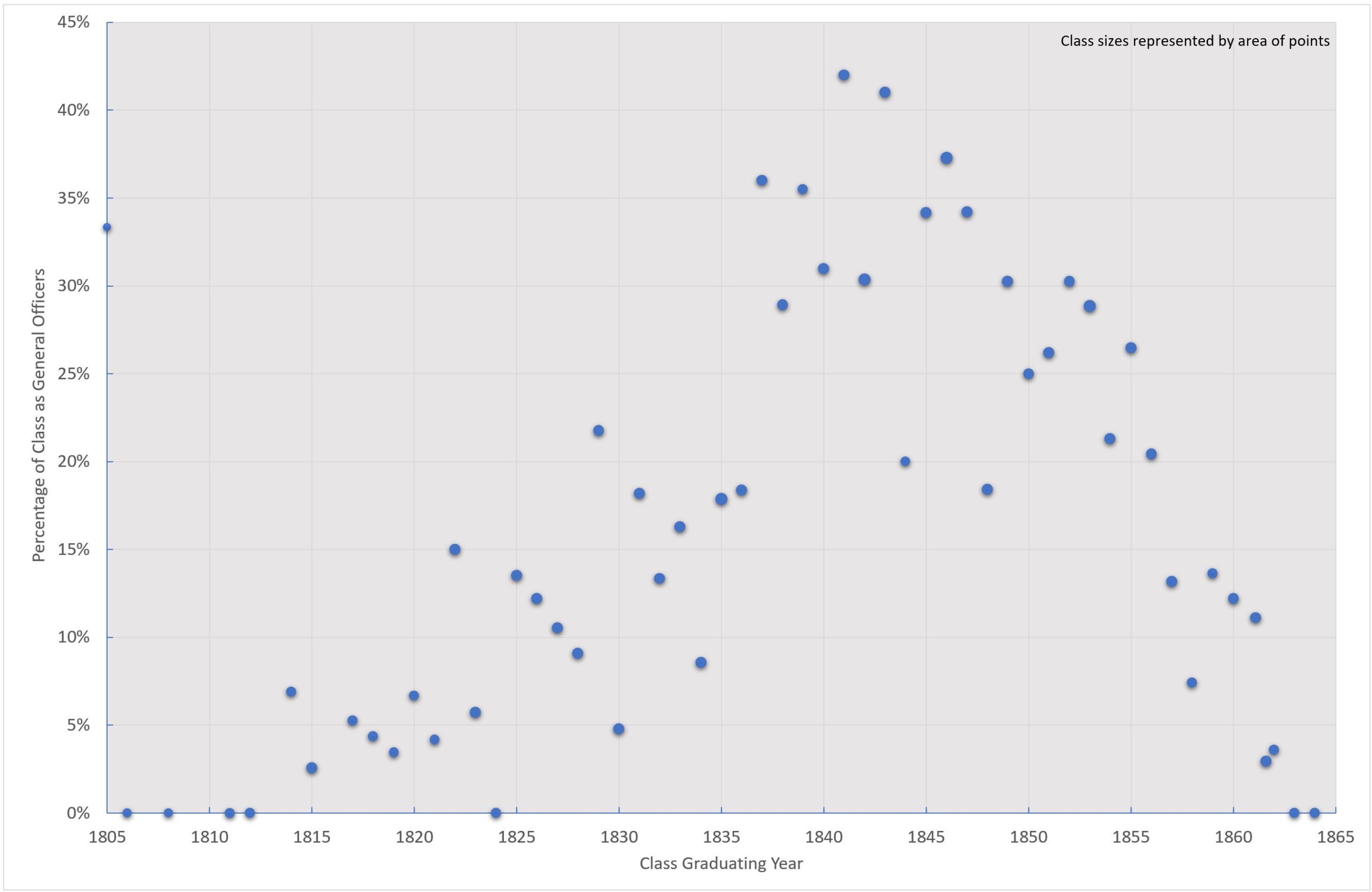

The graph below displays the percentage of cadets by year of graduation that went on to become general officers in the American Civil War:

From the graph, we can see that there were indeed several graduating years that surpassed the mark of the class of 1915, of which 36% of the class became generals. Of these illustrious classes, the classes of 1841 and 1843 had the highest percentage of generals, at 42% and 41%, respectively. Moreover, the class of 1837 (36%) and 1846 (37%) have general percentages rivalling that of the famed class of 1915. While one can jump to crown these classes as “class[es] that the stars fell on,” not all of these graduates served in the Union Army. Should soldiers that fought for the Confederacy count towards the legacy of graduates from the United States Military Academy – I would think not!

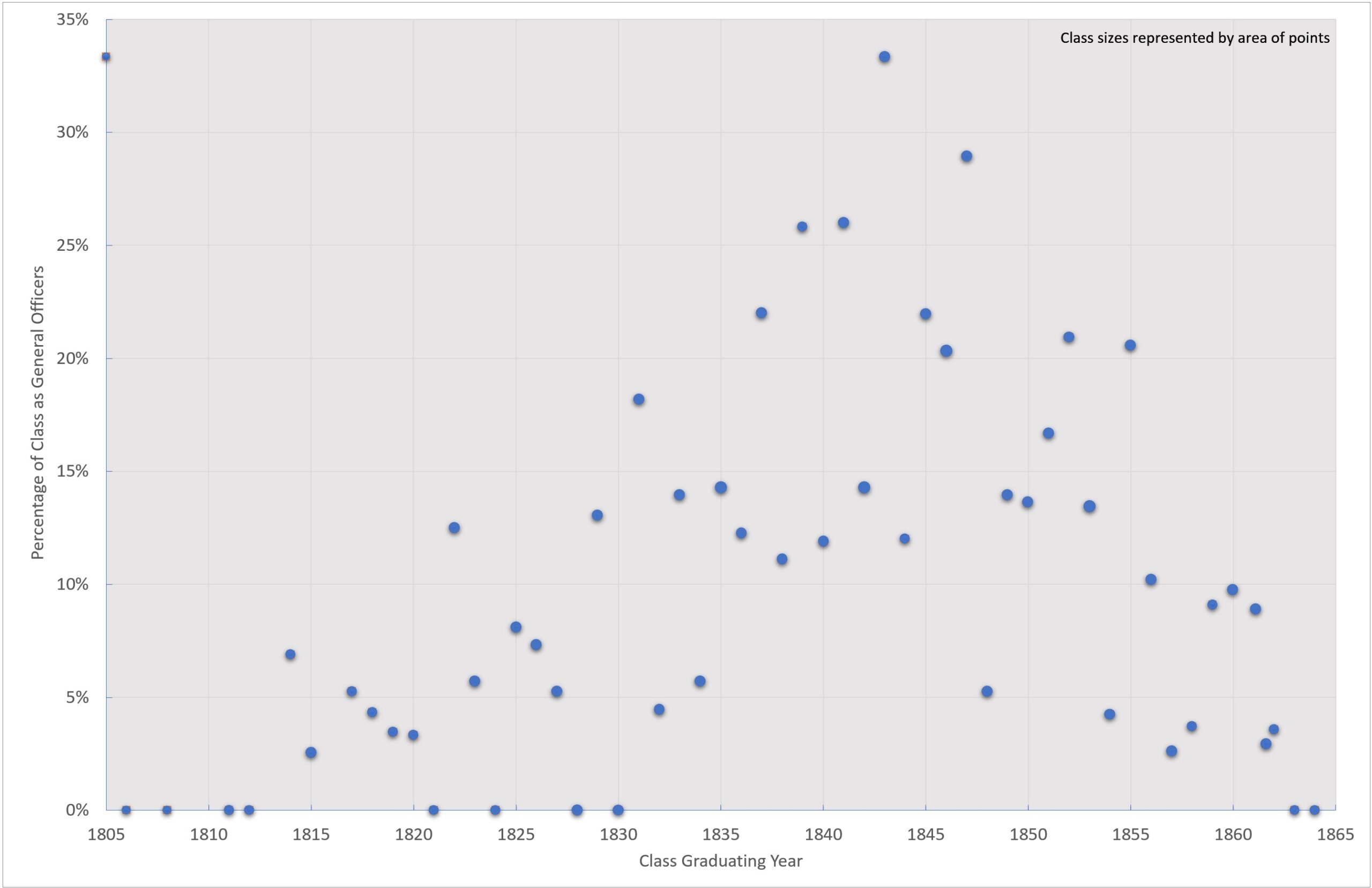

Using this qualifier, we can recalculate the percentage of West Point cadets by year that went on to serve as general officers in the Union Army (both Regular and Volunteer Army) during the Civil War . A bit of a mouthful, but I think this is the fairest comparison:

We see now that the class of 1843, in which 13 out of 39 graduates went on to serve as Union generals, becomes the “class that the stars fell on,” at least until the classes of 1886 and 1915. Among these Union generals from the class of 1843 included 6 brigadier generals, 6 major generals, and Ulysses S. Grant who served as General of the Army and later as the 18th President of the United States.

§

I go back to the quote made by Robert E. Lee at the onset of the war, when he turned down senior command within the Union Army in favor of a position with the Confederate States Army in support of his native state of Virginia.

“I look upon secession as anarchy… but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?”

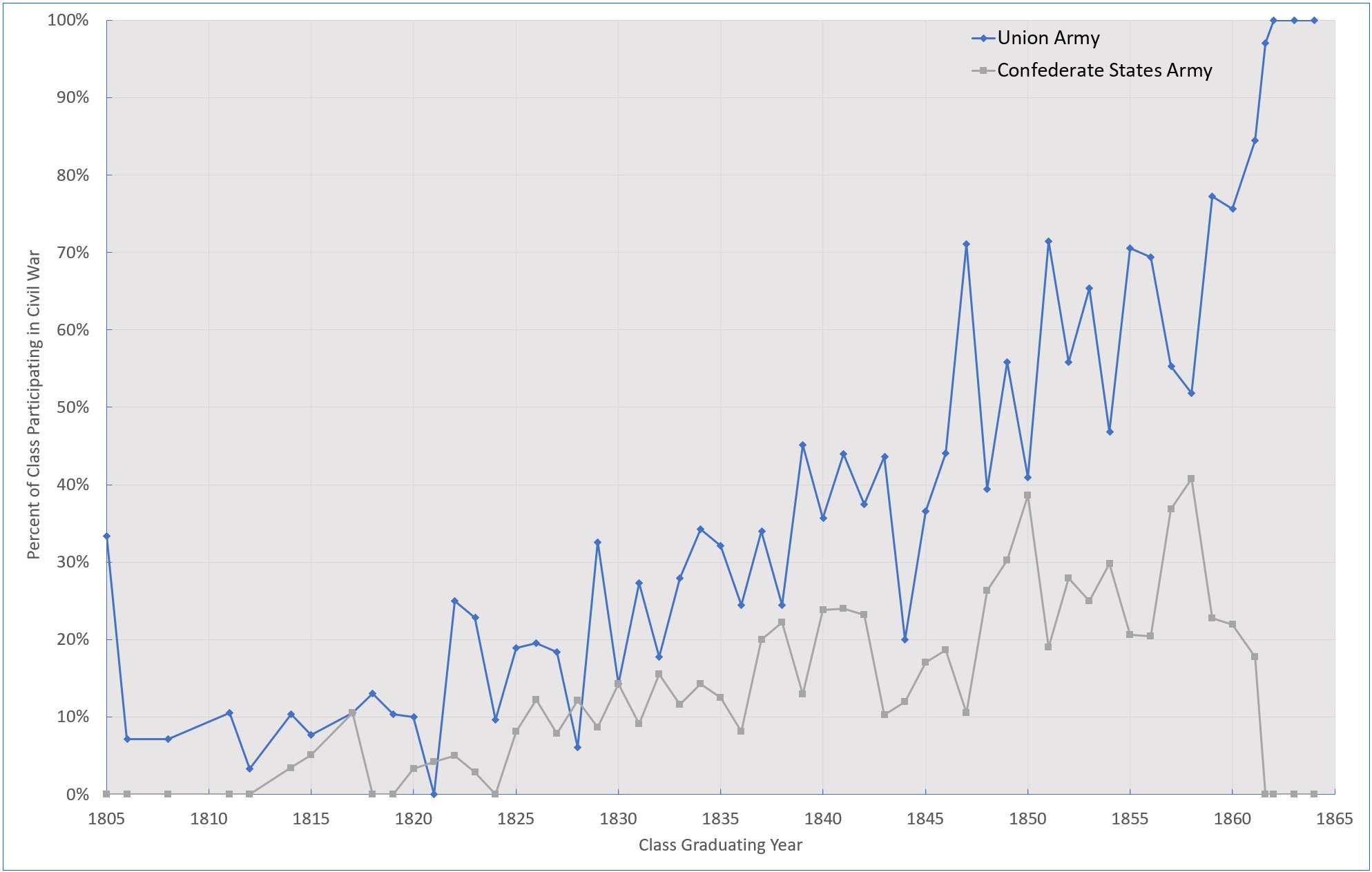

There were conflicts of interest among each of the West Point classes, up until the start of the war when classes consisted exclusively of cadets hailing from the Northern states. The classes of 1850 and 1858 featured the highest percentage of cadets who joined the Confederacy, at 39% and 41% of the class, respectively.

§

The class of 1818 was the first West Point class that was ranked. Since that year, graduating cadets have been ranked on basis of academic performance, military leadership, as well as physical and athletic performance. Numerous highly-ranked cadets have gone on to achieve senior positions in the United States army, such as McClellan (class of 1846, rank 2/59, Commanding General of the U.S. Army). Other acclaimed generals, such as Grant (class of 1843, rank 21/39) and Pershing (class of 1886, rank 30/77) had more mediocre records during their time at the Academy.

While scholastic accomplishment does not necessary correlate well with career success, I wanted to delve deeper into those cadets who went on to become generals – both on the Union and Confederate sides. Did they perform better or worse at West Point than their peers who did not reach such elevated positions?

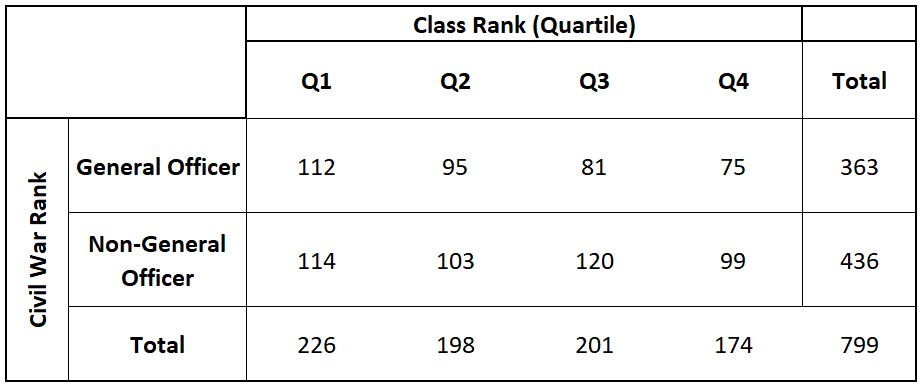

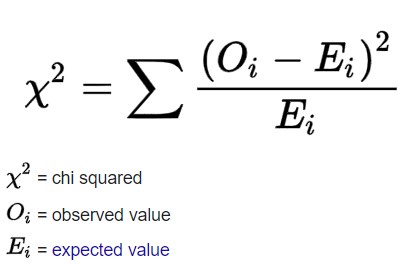

Looking at the data, of the 371 generals on both sides, 366 were ranked during their time in West Point. Within this cohort, 14 were top-ranked in their class, 12 were second-ranked, and 12 were third-ranked. However, for deeper analysis, let us use a chi-squared test, with the null hypothesis that there is no difference between quartile ranks in reaching a generalship position. With three degrees of freedom, the critical value to reject the null hypothesis at a level of p = 0.05 is 7.815.

In the dataset, I used only the ranked classes from 1818 – 1855, with the latter year set as ten years before the end of the war. My reasoning was that it would take some time before a cadet could hope to be promoted to even a brigadier general rank (unless one is George Armstrong Custer, class of 1861, rank 34/34, who became a Major General in the Union Volunteer Army by war’s end).

The null hypothesis is that a cadet’s Academy rank is independent of his civil war rank. Using this assumption, we can then calculate the resulting chi-square test statistic. Across the eight cells of interest, the total test statistic is ~4.59. Since this is below the critical value of 7.815, we accept the null hypothesis at a p value of 0.05.

Therefore, if you were a West Point graduate from the years of 1818 – 1855, worry not about your grades in school, for grades did not determine your career trajectory! Instead, perhaps consider washing your hands, drinking clean water, and staying away from duels!

Reflection

Much attention is focused on the major figures of history that directed policies and led armies into battle, though we should not forget the sacrifices made by the common soldier and average American during the Civil War. The American Civil War remains the costliest conflict as measured by deaths in combat and total casualties in American history. The federal holiday Memorial Day was born out of the nation’s grief in the aftermath of the Civil War, to mourn all the United States military personnel fallen in combat.

Lincoln famously stated, “A house divided against itself, cannot stand.” These remarks, referring to the divisive issue of slavery, were made in 1858 after Lincoln had accepted the nomination as an Illinois state senator. That there has not been a civil war in the United States since May 1865 is a blessing, but Lincoln’s words still ring true to this day, as the nation feels more divided than ever.