Project Timespan

May 2018

Inspiration

Now, I am no cartographer, but I do consider myself an aficionado of maps, especially their ability for abstraction of real-world geography into elegant and clear presentations of terrain. One of my first laser cutting projects was a topographic map of University City, Philadelphia, and while I have since made other topographic maps (including one of Manhattan Island which I will write up), I decided to delve into the world of bathymetry when the thought of a Great Lakes map project occurred to me.

There really is an entire other “world” in the oceans that we have little explored. By some estimates, 80+% of the ocean floor is yet unmapped, and who knows what lies within the depths?

Growing up in Wisconsin, I visited Lake Michigan with regular frequency, and in elementary school, we learned of how the names of the Great Lakes – Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior – spelled out as an acronym the word “HOMES.” I even mastered a piano piece in middle school entitled “Many Moods of the Great Lakes.” All of this is to say that while I may have written this post ostensibly to document my process of creating a bathymetric Great Lakes map, I intend to plumb the depths of history, facts, and notable events of the Great Lakes – something different for each lake!

The Great Lakes

Overview

I will explore each Great Lake in turn, moving from most Western (Superior) to most Eastern (Ontario). I included Lake St. Clair as well, a lesser-lake, certainly, and one that is lesser-known (I had never heard of it before this project, somewhat embarrassingly). One of the more intriguing physical descriptors of a lake is that of ‘residence time,’ or ‘retention time,’ calculated by “the amount of water in a reservoir divided by either the rate of addition of water to the reservoir or the rate of loss from it,” per Brittanica. I do wish we used this analogy in my chemical engineering courses in college – it would have made learning about CSTRs, plug flow reactors, and batch reactors more interesting (just a bit)!

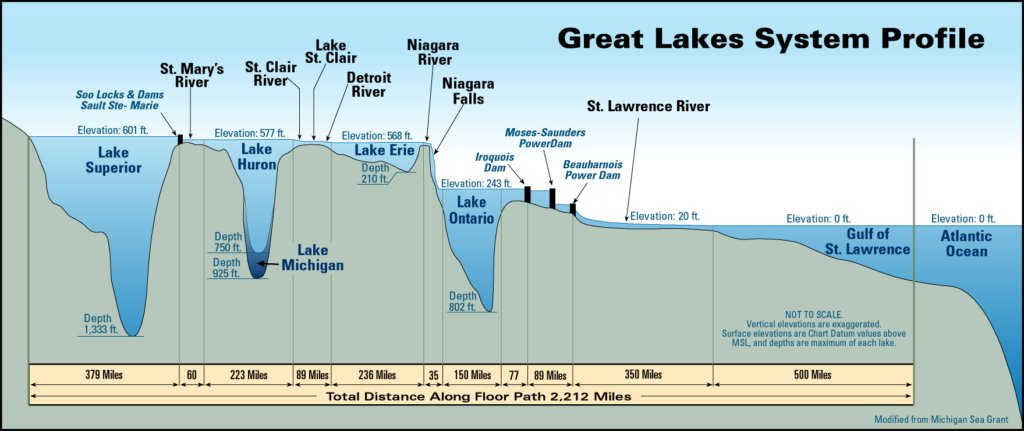

Here is a useful side profile of the Great Lakes System – note the drop in elevation due to Niagara Falls:

Lake Superior

Trivia fact – The total population of the cities and settlements bordering the lake is only 800,000, the smallest number of the Great Lakes.

Name etymology: From French, Lac Supérieur (“Upper Lake”)

Maximum depth: 1,333 ft (406 m)

Average depth: 483 ft (147 m)

Surface Area: 31,700 sq mi (82,000 km2)

Water volume: 2,900 cu mi (12,000 km3)

Residence time: 191 years

While its original name origin may have been derived from its relative geographic location, Lake Superior does boast the major superlatives compared with the other lakes such as depth, area, and water volume. We see that by Percentage of Water Volume of all the Great Lakes, Lake Superior comprises more than half by itself!

With respect to other lakes of the world, the Great Lakes rank 4th, 7th, 8th, 12th, and 18th by water volume. The massive Caspian Sea, holding approximately 18,800 cu mi (78,200 km3), dwarfs the next voluminous lake (the famed Lake Baikal in Siberia); that being stated, one can argue whether or not the former body of water should be considered a ‘lake’ or a ‘sea.’

One cannot introduce Lake Superior without at least bringing up the most famous shipwreck in Great Lakes’ history: the sinking of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald in November of 1975. The ship sank 15 nautical miles off Whitefish Point, along the Southern Shore of Lake Superior in a location known as the “Graveyard of the Great Lakes.” The ship, owned by Northwestern Mutual (coincidentally the company for which my mother works), was caught in heavy seas the afternoon of November 9th, 1975. Reportedly, the phenomenon known as the “Three Sisters,” – in which three rogue waves hits a ship one after another before the water can clear – was responsible for sinking the ship.

The ballad eulogizing the event, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” by Gordon Lightfoot is excellent, if you have not yet listened to it, do yourself a favor. The SS Edmund Fitzgerald, at 729 feet (222 meters) in length, remains the large ship to have sunk in the Great Lakes.

Lake Michigan

Trivia fact – Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake to be entirely within the boundaries of the United States: the others are shared between the States and Canada.

Name etymology: From Objibwa, mishigami (“Large Lake”)

Maximum depth: 923 ft (281 m)

Average depth: 279 ft (85 m)

Surface Area: 22,404 sq mi (58,030 km2)

Water volume: 1,180 cu mi (4,900 km3)

Residence time: 99 years

Growing up in a suburb of Milwaukee, I am by far and away most familiar with Lake Michigan. We spent many a family trip at Virmond Park or Doctors Park or along the lakefront cities of Southeastern Wisconsin. But enough about me: here’s an overview of the lake.

The ancestral lake of Lake Michigan was known as Lake Chicago, a proglacial lake (formed during the retreating of a melting glacier) approximately 14,000 years ago. As the ice retreated northward, water from the early Lake Huron/Erie basins diverted towards the Mohawk River valley. Lake Algonquin would be the next proglacial lake, at around 9,000 years ago and then Lake Chippewa as water levels further dropped. The last major proglacial lake was the Nipissing Great Lakes, comprising parts of now Lakes Superior, Huron, and Michigan; this body of water drained eastward towards the Ottawa valley until finally the present-day St. Clair outlet formed.

Lake Huron

Trivia fact- As Lake Michigan and Lake Huron are conjoined through the Straits of Mackinac, they technically exist as a single lake! The combined Michigan-Huron lake would be the largest freshwater lake by surface area in the Americas, though Lake Superior by itself would still contain more water volume.

Name etymology: Named after Huron people inhabiting region

Maximum depth: 750 ft (229 m)

Average depth: 195 ft (59 m)

Surface Area: 23,007 sq mi (59,588 km2)

Water volume: 850 cu mi (3,543 km3)

Residence time: 22 years

French explorers originally called it La Mer Douce, or the “the calm sea,” although soon the early European maps labelled it Lac des Hurons (“Lake of the Huron”). As with the rest of the Great Lakes, Lake Huron has seen its share of foul weather, none more striking than the Great Lakes Storm of 1913, which remains the deadliest and most destructive natural disaster to befall the Great Lakes region.

The storm began as a November witch, caused by a combination of cold Canadian/Arctic air from the north mixed with warm Gulf air from the South. Over the a few days from November 7th to November 11th, the storm built up strength, with wind gusts reaching 90 mph and waves over 35 feet. Ships sheltering along the southern coast of Lake Huron experienced the worst of the damage, as northerly winds swept eastward across the whole of the lake shore. In total, twelve ships were lost with all hands, including eight in the depths of Lake Huron.

As an aside, I wanted to bring up Georgian Bay, a bay of Lake Huron located entirely within the borders of Ontario, Canada. To be frank, I had not heard about this body of water until today when I wrote this section of the post…

The Georgian Bay contains the Thirty Thousand Islands, the world’s largest freshwater archipelago. With plenty of fishing, kayaking, hiking, and swimming, this place now finds itself high up on my places to visit!

Lake St. Clair

Trivia fact: Lake St. Clair is known as the “Heart of the Great Lakes,” and it does look somewhat heart-like, I suppose.

Name etymology: From French, Lac Sainte-Claire

Maximum depth: 27 ft (8.2 m)

Average depth: 11 ft (3.4 m)

Surface Area: 430 sq mi (1,114 km2)

Water volume: 0.82 cu mi (3.4 km3)

Residence time: 7 days

Although Lake St. Clair isn’t technically part of the Great Lakes, as there does not exist, to my limited knowledge, a corresponding set of “Lesser Lakes,” I wanted to give it some airtime! One characteristic I immediately noted about the lake is its shallow depths, with an average of 11 ft, which is even shallower than that of the shrinking Aral Sea. The lake was named by the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier as his expedition sighted it on August 11, the feast day of St. Clare of Assisi. An earlier name for the lake by the Mississauga people was Waawiyaataan (From Anishinaabe, “the whirlpool”) which I find to be an awesome name!

Given its importance in ensuring an uninterrupted waterway for shipping, Lake St. Clair has undergone extensive dredging of its lake bottom, with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredging a 27 foot deep navigation channel for lake freighter passage.

Lake Erie

Trivia fact: There are at least 2,000 shipwrecks in Lake Erie, the most of the Great Lakes.

Name etymology: From Iroquois, Erielhonan (“Long tail”)

Maximum depth: 210 ft (64 m)

Average depth: 62 ft (19 m)

Surface Area: 9,910 sq mi (25,667 km2)

Water volume: 116 cu mi (480 km3)

Residence time: 2.6 years

The tribal name of the Erie tribe stems from the term erielhonan, an Iroquoian word. Although we think of “Iroquois” in the context of the Iroquois Confederacy, of which the main 5 nations were the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca (the Tuscarora people would join later), many other native tribes spoke languages considered part of the Iroquoian-language group, including the Erie people. The Erie people were also called Chat, or cat, by the French, possibly referring to the long raccoon tails worn on their clothing.

While I mentioned the Three Sisters above in context of rogue storms and the sinking of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, the term also refers to the three major agricultural plants harvested by the native peoples of North America: winter squash, maize, and beans. The Erie people, too, were known for their agriculture and their fur trade. Eventually, they ran afoul of their eastern Iroquois League neighbors by accepting Huron refugees fleeing from Iroquois attack. In 1654, the whole of the Iroquois Confederacy went to war against the Erie people, and over the next five years the Confederacy destroyed much of the tribal structure with remnants being absorbed into the Seneca nation.

Lake Erie is also home to the most famous sea monster this side of Loch Less, that of the monster “Bessie,” also known as “South Bay Bessie” or “The Lake Erie Monster.” Various sightings of the creature(s) throughout the centuries have provided various descriptions such as shaped like a large sturgeon with arms, a long serpent or with a dog-shaped head and pointy tail.

Lake Ontario

Trivia fact: More than sixty people have swum across Lake Ontario – the first, Marilyn Bell, was only 16 when she accomplished the feat in 1954.

Name etymology: From Huron, Ontarí’io (“Great Lake”)

Maximum depth: 802 ft (244 m)

Average depth: 283 ft (86 m)

Surface Area: 7,340 sq mi (19,000 km2)

Water volume: 393 cu mi (1,640 km3)

Residence time: 6 years

Although the smallest Great Lake by surface area, Lake Ontario nevertheless is the 13th largest lake in the world. Given the lake’s depth – an impressive 800 feet at its deepest – the lake cannot completely freeze during a winter cold. Nevertheless, in recorded history, Lake Ontario has frozen over five times: in 1830, 1874, 1893, 1912, and 1934.

Fishing plays an important role in the industry of the Great Lakes. Unfortunately, the wildlife of Lake Ontario has suffered considerably due to human involvement, and Lake Ontario has the most extirpated species of any of the Great Lakes, with several species of fish, including bigeye chub, lake trout, and Atlantic salmon lost from its waters.

Lake Ontario is home to the Golden Horseshoe region of Canada, containing the Greater Toronto Area and accounting for more than one-fifth of Canada’s population with more than 7.8 million people residing in its boundaries (Core area in red, Greater Golden Horseshoe in green):

In addition to the major city of Toronto, other major cities include Hamilton and Oshawa, with significant steel and automotive industries, respectively.

Project Overview

Okay, well, that was a lengthy diversion from the project, though I do hope it was of some appropriate combination of entertainment and edification. Onto the project log, where I will go over the materials, design, and processing of the Great Lakes map before a final unveiling. Enjoy!

Materials

Studio wood panel, 16″ x 20″ x 1.5″

Wood stains, blue and brown

Hmm, and a laser cutter, I suppose! I don’t remember the exact colors/brand of the wood stains I used, as I purchased them from a local hardware stool in West Philly. I reckon either Miniwax or Varathane.

Design

While designing the map, I wanted to keep the features as natural as possible, which meant forgoing any representations of man-made structures such as roads or cities. Instead, I opted to include only rivers and lake boundaries in the map. While bathymetric layers were a given for the Great Lakes themselves, I decided to not depict corresponding land elevations. In doing so, I focus the observer’s attention on the water depth layers, although my primary reason for not creating a combined topographic-bathymetric map was due to time constraints.

I used publicly-available data from NOAA (National Centers for Environmental Information), which provided me with ESRI shapefiles of all the Great Lakes with the exception of Lake Superior. More than three years after finishing the project, I see that the Lake Superior bathymetry map is still marked as incomplete. I cannot remember where I eventually found a usable bathymetric dataset for Lake Superior, though I’m sure it can be found with a few online searches.

For the rivers, I managed to find a dataset which provided the lake borders and river flow paths:

I chose not to label any of the features in the map, in part given the already numerous rivers and small lakes that dotted the area. I’ve always liked the contrast between natural Baltic birch and blue stain, so those were the two “colors” I used, other than staining the frame a medium-brown tone.

Processing

Given that the deepest portion of the Great Lakes is a 406 m point in Lake Superior, I decided to use 50 m bathymetric depths. In other words, the shallowest depth would be from 0 – 50 m, the next from 50 m – 100 m, and so on. Thus, the Great Lakes would consist of the following number of layers: Superior – 8 (considered 400-405 to be part of the 350 m depth), Michigan – 6, Huron – 5, Erie – 2, Ontario – 5.

The astute observer would also note that depths between these bodies of water are not technically equivalent. For example, the surface elevation of Lake Superior is 600 feet (180 m) above sea level, whereas the surface elevation of Lake Ontario is 243 feet (74 m) above sea level. Thus, elevation-wise, there is a two-layer difference across the map that is not depicted (this would further complicate construction of a topographic-bathymetric map).

I wanted the depths of the water to become darker with the layers, so I used mineral spirits to dilute the blue stain, with progressively dilute coloring with shallower layers. The resultant effect was more muted than expected, though noticeable to the discerning eye.

For the most shallow layer of water, I needed to stain all of the underlaying Baltic birch ply blue as there were small silhouettes of lake bodies peeking from behind throughout the map: even though I framed the map to limit exposure of the Atlantic Ocean, a piece of the Chesapeake Bay managed to sneak its way into the far corner of the map! As most of the map was only “one-depth” thick, I could be more judicious in my use of material for subsequent layers.

The tricky aspect of assembly was to ensure the proper layers of islands or local prominences underneath the surface. For example, for Lake Nipigon, located directly above Lake Superior, there were six additional small island pieces to glue on the map! Thankfully, the thirty thousand islands of Georgian Bay were too tiny to depict.

Final Result

Lessons Learned & Improvements

I made this project as a gift for my parents, and while they very happy with the end result, I have thought of many areas of improvement:

1. Blending oil stain for water depths: I used mineral spirits in an attempt to dilute down the blue oil stain in depiction of shallower lake depths, and the end gradation is of minimal contrast. A simpler strategy would have been to mix the blue stain with a white oil stain for the various depths.

2. Making my own frame: I do enjoy using Blick’s Studio Wood Panels for topographic/bathymetric maps, but in this case there were reinforcing staples unfortunately placed at the corners of the frame. Now, since I am really using the backside of the wood panel as the front, it is not Blick’s mistake but rather a lack of oversight on my part; I pulled the staples out but used

3. Adding a back design: I intended the finished project to function as wall decoration, but custom rastered image and an engraved dedication message on the backside would have been even better.

4. Incorporating epoxy as river/lake infill: Blue epoxy resin poured into the crevasses of the rivers and negative spaces of the lake depths would make the map “pop!” I would probably then vector-etch through the material thickness for the rivers as well.

I do intend to revisit the Great Lakes again as a project, and perhaps with a larger frame I can add in additional features.

Reflection

There is a famous quote by the Greek philosopher Heraclitus: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.”

This statement can be applied too for other bodies of water such as lakes. One swimming in Lake Ontario in the 21st century may be frolicking in water that comprised a portion Lake Superior more than 200 years before!